Papuşa survived the Romani Holocaust – now she begs in Stockholm

Uppdaterad 2015-12-02 | Publicerad 2015-11-29

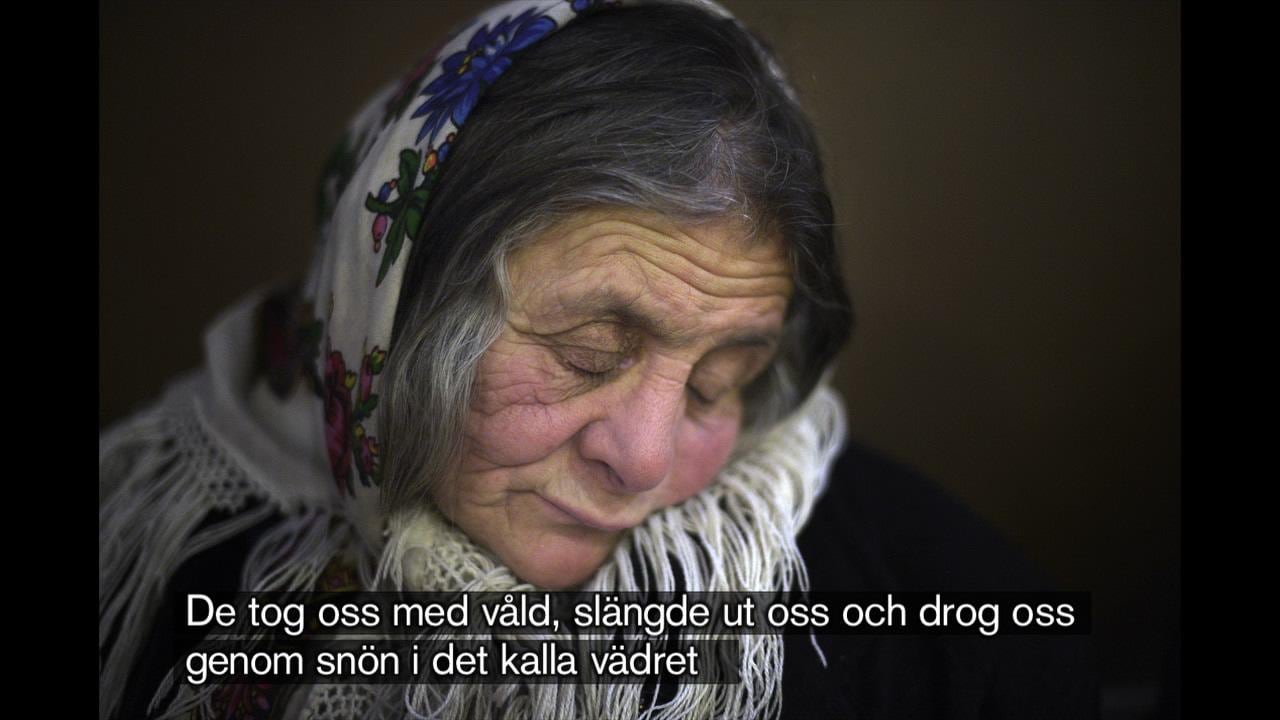

Papuşa Ciuraru, 81, survived the genocide of the Roma people during the Second World War.

She is now a beggar on the streets of Stockholm.

– It's freezing. But I do it for my dear grandchildren, she says.

An old woman is begging by the entrance to Kungshallen, a food court at Hötorget in central Stockholm. Her face is wrinkled and her body is weighed down under her two coats.

The old woman would like enter the food court to warm up her frozen fingers. Approach the guests with her empty coffee cup and ask for some coins.

But every time she has tried to enter, a waiter or a guard has come up to her:

– You have to leave!

– You scare our guests!

The woman's name is Papuşa Ciuraru and what neither the restaurant guests, nor the waiters know is that she is one of the great survivors of the 20 century.

Looking at her ID, you would think that Papuşa is born in 1945. That is not true. The date was set by Romanian authorities at the end of the Second World War, when there was chaos in Europe with far more refugees than today.

In fact Papuşa Ciuraru was born several years earlier. Around 1934, according to people close to her. That means that Papuşa - her name means "doll" in Romanian - is around 81 years old.

She grew up close to the town of Buhuși in northeastern Romania. Her father and grandfather were skilled metal workers and the family were nomads, travelling from village to village with their horse and wagon selling copper kettles.

On a winter day in 1942, Romanian policemen approached their camp and started shooting.

– I was only a child when it happened. But I remember clearly that there was a lot of snow outside. My mother and father quickly gathered us children, she says.

It is called porajmos or the Roma Holocaust. The romani people were, apart from the Jews, one of the groups that suffered the Nazi extermination policy most severely during the Second World War.

Tens of thousands of Roma were massacred by SS troops on the Eastern Front or killed in the gas chambers. Others were left to Hitler's allies to deal with.

Many of the victims could not read or write. The crimes committed are not sufficiently documented and the suffering of the Romani people was for many years not recognized. It was as if the porajmos had never happened.

Even today, no one knows exactly how many Roma people died during the war. Some historians claim about 250,000, others half a million.

The Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu, an ally of Hitler, decided to expel the Roma people to Transnistria. An area conquered from the Soviet union in present Moldova and Ukraine, to where tens of thousands of Jews already had been deported.

Papuşa's family were robbed of their belongings and forced out on a 200 kilometer long march.

– I remember how my mother carried me through the snow on her shoulder. We had no idea where we were going or what was going to happen to us, says Papuşa.

It is the end of November and the winter has taken hold of Stockholm. Papuşa move her frozen fingers back and forth. Last year, she left Romania together with two of her children to beg on the streets in Sweden.

– I love my grandchildren. I cry when I can’t be with them. But I have to support them so that they can stay in school. Nobody gives you anything in Romania, that is why I have come here.

Papuşa says she earns thirty or forty kronor a day in Sweden. She eats only if someone offers her something and saves every penny.

– People used to give more in the summer. Now, it has become more difficult or us. But still, there are kind-hearted people in Sweden.

The soldiers deported Papuşa’s family and the other Roma people to a piece of infertile land wedged between two rivers.

– We spread out corn stalks on the cold, frozen ground and slept on them, she says.

During the days, she was sent out along with the other children to try to snatch potatoes and sugar beets.

– We ate everything we came across, but it was not enough. Children and old people were the worst affected, they starved and froze to death and died of diseases like typhoid.

Out of the seven siblings, only Papuşa and two of her sisters survived the deportation.

– My brother and my sisters were left on the ground like all the other dead. There were large fields, but no place to bury them. They remained there until the dogs came.

Why did you survive?

– It was God's will. Only he knows why things happen.

Papuşa walks Drottninggatan, one of Stockholm's major shopping streets, with a beggar’s cup in her hand. Her legs hurt, but still, she walks up to everyone she meets.

– Begging is in my blood, she says, laughing.

Christmas lightning is everywhere, generosity nowhere. A woman shakes her head when Papuşa approaches her. A man stares into his smartphone.

A boy laughs nervously.

– I say "thank you", I do not steal and I am not being unkind to anyone. Some give, some do not. That's the way it is.

When she first arrived in Sweden, Papuşa lived with a group of other Roma people from the same part of Romania in a parking lot in Kista in northern Stockholm.

One day in April, a 25-year old Swede attacked the group. He poured fire-lighting fluid on one of the women's clothes and started shouting in a threatful way.

– Everybody was running and some people stamped upon me. We lost all of our belongings. I was so scared, says Papuşa.

After nearly two years, the Nazis were pushed out of Transnistria by the Red Army. But the Russians were no liberators. They shot in the air and forced Papuşa’s family to flee once again – back to Romania.

– We were all walking in a long row. We were walking for a year. No one knew the way back or how we could cross the rivers. We got lost several times and had to turn back. We were barefoot, and many died along the way. Even today, people call it the "gypsies 'road".

When they finally reached the Romanian border, they were once again fired upon. Now by Romanian soldiers.

– Somehow we still made it through.

What was it like to come home?

Papuşa looks at me in surprise.

– My God, what do you think? Awful! We were starving and had nowhere to live. But someone gave us tents. A little help arrived, and slowly things got better.

Papuşa married a Romani man from the city of Iași and had twelve children, nine of whom are still alive today.

Romania went from fascism to communism and the dictator Ceauşescu ruled the country with an iron fist.

For Papuşa, little changed.

She continued to walk from village to village selling copper kettles, as her family used to before the war.

– There were good times and bad. Life is like the weather, you know. It goes back and forth.

It is a late, dark afternoon and Papuşa has not eaten all day. We enter a McDonald's restaurant and order chicken burger and fries.

The 25-year-old man who attacked the Roma people in Kista was sentenced to probation, but is already suspected of new crimes against Romanians in Sweden.

Papuşa is forced to sleep outdoors, like she used to 70 years ago.

This time she doesn't put corn stalks on the ground but pieces of cartons that the fruit vendors at Hötorget have left behind. She wraps herself in the blankets that some aid workers have given her and curls up between her son and daughter on the steps of the Concert Hall, where Stockholmers flock on sunny spring days.

Before she falls asleep, Papuşa prays to God that the police will not come and force them to leave or that some drunk people will menace them.

– It's freezing. My head aches, I can't move my toes and it is so difficult to get up in the mornings.

She hopes to get a bed at a hostel run by a charity for a few nights every now and then. But no matter what happens, she will hold out. For her grandchildren.

Papuşa is one of the last witnesses of one of the Second World War’s least known genocides. But she belongs to a people that have never been able to write down their own history.

All of her life, she has wanted to learn how to read and write. Spell out her own name, P-a-p-u-ş-a.

Survivors of the deportation are entitled to a small pension in Romania. Papuşa filled out a form a couple of years ago and put the letter “X” instead of a signature at the bottom, but has not yet received any response.

– That is why I tell my grandchildren that they need to learn how to read and write. I don’t want them to be helpless like me.

She shows me her hands with her finest possessions: three copper rings that her grandfather once made, that the soldiers never stole.

– They are my memory of our history. My link to the past.

Still, she cries whenever she thinks of what happened to her people more than 70 years ago.

– We are Roma people. Sometimes I can’t help but wonder what is wrong with us....

She coughs.

– God forbid that it happens again.

Papuşa's legs have become stiff after being seated too long inside the warm hamburger restaurant. She apologizes and says that she needs to walk around for a little while to stretch them.

Almost immediately, a young employee approaches her:

– You cannot beg in her!

Papuşa quickly heads back to her table. Clearly, the young woman in the restaurant does not know who she is or what she has gone through.

And even if she had: would that have made any difference?

Life is like the weather, it goes back and forth. Sometimes it is as raw and cold as today, but Papuşa Ciuraru is a survivor. She will endure.